The Fight for Survival of the Arts and Culture in Puerto Rico

Artists collaborate in order to continue doing art amidst the demise of cultural institutions.

A few months before the pandemic hit, Leticia Berdecia, 21, started questioning parts of her identity: her status in Puerto Rico, her background, and her body — her skin in that ambiguous color, almost turning to brown, that becomes the biggest signifier that you come from a colonized space.

Starting a journey of self-exploration, she visited Guadeloupe. Accompanied by two friends that lived on the Caribbean archipelago, she attended a local carnival, in which community members walked and danced for five hours — a performance meant as an act of resistance because of its reclamation of the space through artistic and radical expression. When Leticia returned to her friend’s home that night, she burst into tears, overcome by an inarticulable feeling of absence in her body. Her feelings about identity were by no means resolved, but through her sobs, one thing became clear: she wanted to do something for her country, and for the wider Caribbean region, and she wanted it to be through the arts.

When she returned to her hometown in Cayey, Puerto Rico, she founded Archivos del Caribe, which translates to “archives of the Caribbean.” Leticia was not yet sure what the project was going to become but she was driven by a desire to provide and hold open cultural space for her Caribbean siblings. On Instagram, she saved the username “archivosdelcaribe.” Leticia invited me to become a part of the project, as it grew into something between a community organization, a digital archive, and a space for identity exploration. The project follows a decolonizing and antiracist perspective through photographs that show the realities of Black and Brown people in Puerto Rico often masked in history books. It also includes educational resources from film, articles, and academic readings, and contemporary literary material we have written, seeking to reject and replace traditional modes of education.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_fmff3B_-O/

On an archipelago that is known as the oldest colony in the world, with a financial crisis caused by political instability, natural disasters, corruption, and constant individual suffering, the arts and culture become a necessity. Artists, leaders, and organizers create with the purpose of seeking justice for themselves within their living space. Puerto Rico, despite all the suffering, has a passion that connects it to the rest of the world.

In April, we started formulating ideas and plans, with most of our content living solely on Instagram. When the time came to build a website to enable further outreach, we searched for funding. We turned to the government agency specifically dedicated to promoting projects like ours: the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP), which stands for the Puerto Rican Culture Institute. But like many independent organizations in dire need of government support, we could find none. The ICP’s website offered no information about applying for funds. After months attempting to find connections to the ICP or some other government office that could provide economic support, we turned to our personal savings. As college student workers, it was a sacrifice.

The demise of government cultural institutions

The ICP was founded in 1955, soon after Puerto Rico became an “Estado Libre Asociado’’ — a free associated state — named by Congress and the Popular Democratic Party (PPD) in an effort to obscure the colonized position in which the United States held the territory. With this label, which the United States does not use, Puerto Rican officials had a perception of solving the political turmoil and making room for celebration, which meant including the arts and honoring the culture, even if it was from a colonized and racist perspective. Part of the ICP’s mission is to “investigate, conserve, promote, and divulge Puerto Rican culture in its diversity and complexity.”

The budget for ICP and other cultural institutions in Puerto Rico has decreased significantly in the last decade.

“[The ICP budget] accounts for .007% of the Government’s total approved budget, despite all that culture provides to us at a country-level”, said Carlos Ruiz Cortés, the executive director of ICP, in a hearing of government transition.

He highlighted the financial struggles of the 6 other cultural institutions in Puerto Rico. In total, they represent .016% of the government budget according to Ruiz Cortés.

This has an effect on Puerto Rico’s cultural patrimony. Recently, NotiCel reported that the ICP will be closing their General Archive and National Library by 2023.

The state of the ICP is a reflection of Puerto Rico’s broader economic crisis. A debt of over $74 billion dollars has caused extensive problems in various areas such as the Department of Education, healthcare, natural resources, as well as the arts.

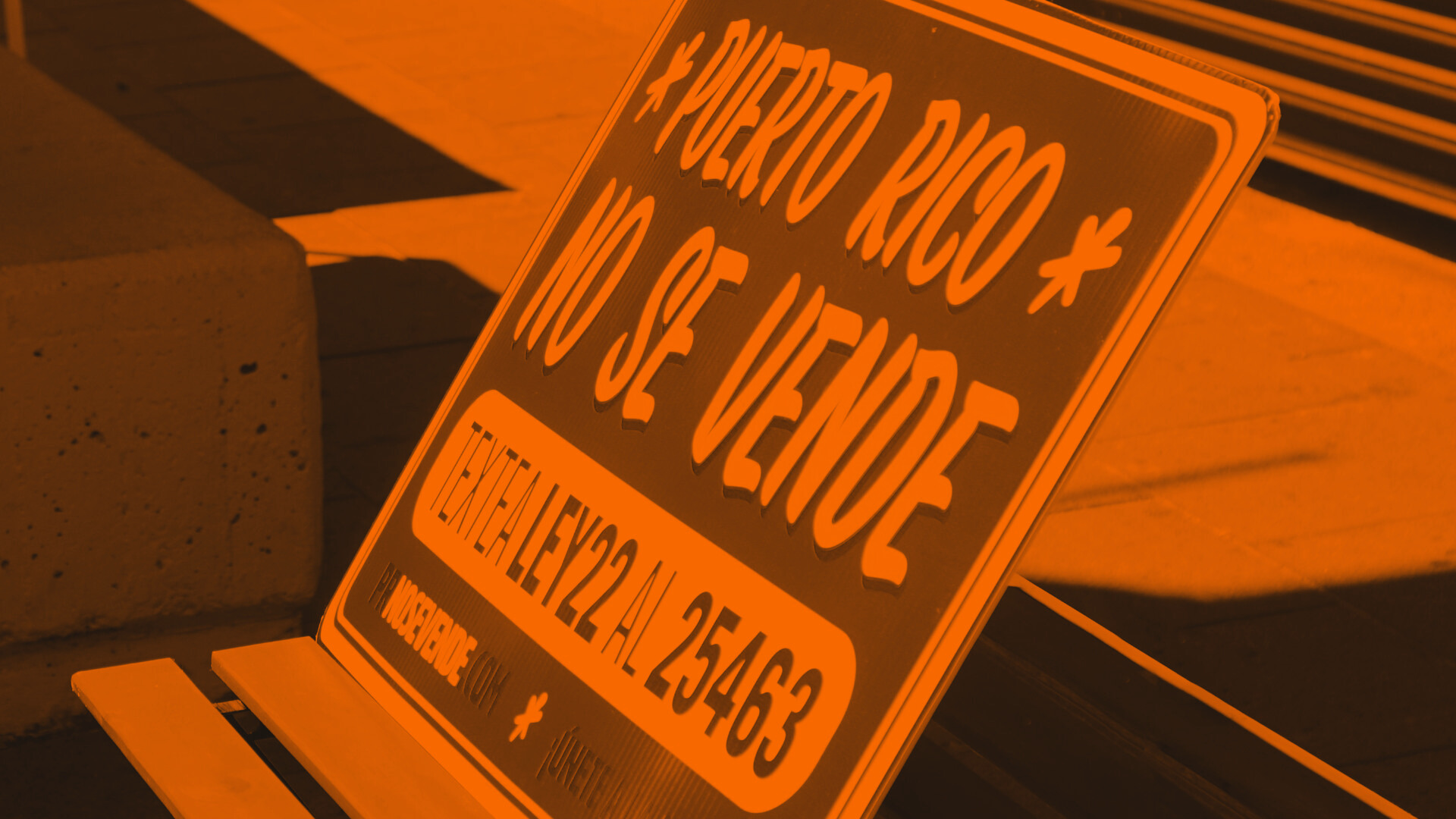

This economic decline is perpetuated by the “PROMESA” law which the United States Congress enacted in 2016. The law pushed a financial oversight board to control the archipelago’s budget without the consent of citizens. And the ICP has faced severe budget cuts under PROMESA oversight with the appointed Fiscal Control Board (FCB.)

The funding for direct services decreased by 77% in the last decade, according to a report by Dr. Javier J. Hernández Acosta and Cristian Gómez Herazo for Inversión Cultural. These services include operating costs and subsidies for conserving, promoting, and financing cultural activities.

The funding that remains available is only released under strict criteria that almost no new initiative or early career artist can meet. The numerous bureaucratic hurdles placed before artists allow the government agency to skirt its proclaimed obligation to the arts during a time when those arts are more needed than ever.

Partisan interest over culture

The offices of the ICP are located in one of many buildings left ravaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017. In historic Old San Juan, the building looks abandoned, with layers of paint falling off the walls and ceilings that leak when it rains — as it often does in the tropics. Few employees walk the halls. Silence fills the empty space.

“There are magazines and other published works stored with mold, the building is not in good condition, there are many complexities in place,” said Abdiel Segarra, 36, a former employee of the ICP.

Working for three years at the institute, he said the structure knocks you down due to the “challenges of all the things that have been done wrong for many years.”

Segarra explained that, from what he experienced, the ICP could create funding for artists and consider having their building in functional conditions. But it becomes difficult when every decision is politicized. The ICP functions in a hierarchy that is vulnerable, as most of the island’s institutions, to political turmoil: the director changes frequently when new politicians come into power. In Puerto Rico, the elected governor tends to name new officials across offices and departments, ones that align with their political views.

“The political party in power influences how the ICP will be managed and that makes it inconsistent.” shared Segarra. “The political agendas run us over and no one asks “why is this not working?’”

The absence of an inclusive artistic vision results in many constraints and blind spots. Young artists on the rise are not even on the radar of the ICP unless they follow the traditional art standards: paintings and sculptures that can be easily interpreted and do not challenge injustices.

“In recent years, they [ICP] has been trying to support artists as entrepreneurs,” Segarra said, adding that it is not working. “The ICP’s job is not to make the business-people, it is to generate accessible artistic policies.”

What artists are expecting of the ICP is only what the institution should be doing. Yet, our experience is that they are unable to help artistic groups. “One never fully trusts the government. We ask them to do what they are supposed to, and then we hope for the best.” Segarra expressed, with hopes of seeing conversations from artists that the government will listen to.

Self-determination is the key

“I trust the initiatives began by artists,” said Luis Rivera Jiménez, 23, co-founder of Albania Galería, a small, independent art gallery in San Juan.

The gallery shifts the traditional notion of where art should live. It is on the second floor of a house, the walls are still white, but the floor is gray with splatters of paint. There are nine paintings by local artist Armig Santos, three on each wall, the fourth wall being the entrance. The canvases are small, with dark colors but separate figures that incorporate symbols of our every day: a knife, Adderall, a glue stick, and a Yankees hat, a symbol of Puerto Ricans that connects us to the diaspora, particularly all the people that have moved to New York.

“It’s the creatives doing the work the government is meant to be doing. The key is in self-determination,” added the art history student.

Rivera Jiménez is originally from Luquillo, a beach town about 40 minutes east of San Juan, he attends the University of Puerto Rico in the capital. As a student, he has been able to learn about some funding options for artists and scholarships, which are only found by word of mouth around San Juan; online information about application criteria is often scant if available at all.

Even with some insider knowledge of the arts and culture in Puerto Rico, Rivera Jiménez has struggled to find support for his ideas, especially from established art institutions.

“I have had encounters in the traditional art world that were not pleasant.” Rivera Jiménez said, discussing his experiences as a Puerto Rican and Dominican man in the artistic community that tends to be white and affluent.

As a reaction, he founded an artistic space that he describes as “for you, for me, for everyone,” using the gender-neutral “todes” in Spanish. Albania Galería came to life independently, organized by a group of young artists wanting to break the traditionally exclusionary confines of larger galleries and museums. The gallery space is located in a house in Río Piedras, a poor neighborhood with a mix of elderly people and college students.

Rivera Jiménez told me that, alongside the ICP, the few major museums in San Juan consistently foreclose possibilities for young artists challenging the art world’s conventional wisdom: the white cube containing predominantly artworks that present just one perspective of the world, that of older men in a somewhat upper-middle-class position.

“There is a privilege that allows them to decide what is culture and what is not,” he said of such institutions, all of which, unlike his gallery, are located in gentrified neighborhoods of San Juan like Santurce and Miramar, once predominantly inhabited by immigrant communities.

Few materials about movements of resistance that occurred before the transformation of the area are made accessible. How the arts have been used as a political tool in Puerto Rico, rejecting gentrification as well as gender norms, colonialism, and racism, is hidden. Yet, in this indie scene, photographers and other artists create their own materials and share them, out of a wish to keep the true lived experiences alive.

“If the government would see art as an opportunity for a market, they would respond to it.” Rivera Jiménez said. “That is why there is still a lot missing from the ICP.”

If the government does not acknowledge the diverse age ranges, styles, conversations that the arts bring, they will continue to not prioritize it in their planning. Until this step is taken, artists are forced to create independently, make sacrifices, and some are even forced to move.

Sustaining ourselves through collaboration

Faced with unreliable government support and unsupportive established institutions, the arts and culture movements nonetheless find inventive ways to survive. It has been up to the community leaders and organizers to preserve the histories of Puerto Rico through art. Unconventionally and autonomously, collectives have found their best option is to rely on each other and the communities in which they live and create.

Independent organizations, such as Piso Proyecto, Taller Malaquita, and Demoliendo Hoteles have been doing just that. Piso Proyecto “uses art and movement improvisation to create alternative methods of relating, verbalizing, codifying and embodying ideas,” according to their website. For a decade, PISO has been sustaining itself thanks to collaboration, cooperation, and an alternative economy.

Taller Malaquita is a woman-led platform for collaborations between visual artists, designers, and creators across the Caribbean and Latin America. They had closed down a physical location due to lack of funding but, through community efforts and donations, have found a new temporary space to continue their work, which includes artist residencies.

Demoliendo Hoteles, whom I had the chance to speak with, is a literary magazine intent on giving a forum to rising authors. Currently, their work is online but they are working on releasing print editions.

“For Demoliendo Hoteles, we didn’t even think of going to the ICP for support,” the magazine’s editors told me.

The editorial team of this magazine used their own savings to fund the project — a privilege they acknowledge is unavailable to most independent Puerto Rican arts initiatives.

One of the few independent efforts that currently exist to support artists is Beta-Local. Legally, they are a non-profit organization. In spirit, they are a space run by artists that provides as much support as other artists need. The directors Nibia Pastrana Santiago, Michael Linares, and Pablo Guardiola told me they want to make the process of receiving economic assistance easier for artists in Puerto Rico.

“At Beta we want to require as little paperwork as possible. This is for artists to have access,” said Michael Linares of Beta Local told me via Zoom Because of Puerto Rico’s political status, not having a facilitator makes applying for funds in the U.S. or internationally more difficult. Beta-Local gives scholarships and emergency funds for artists and some collectives. The funding they provide comes from private organizations. None of their economic support available for artists comes from the federal government.

Besides the ICP’s lack of economic resources, their priorities are not aligned with the artists and creatives currently pushing for a new vision of “puertoricanness” that rejects the embrace of Spain’s colonial legacy.

“Puerto Rico has the privilege of being a place of resistance by nature. All of our generations have their own struggles, but we have fights in common. We can’t simply fall in the trap of ‘it’s the system’s fault’ because all of us go through that. We know the system doesn’t work,” added Linares, referencing the generational gap between us.

“We have to turn to reclaiming and self-sufficiency; we find that in small, independent, and solid projects.” From 2014 to 2020, Sofía Gallisá served as co-director of Beta-Local. During her time there, Gallisá saw a need from the artists in Puerto Rico due to the lack of support elsewhere. “This problem is repeated among organizations.” she said, referring to the economic needs.

“We always had the conversation that non-incorporated organizations would not have access to most funds.” “That doesn’t mean Puerto Rico is not a great place to make art.” Gallisá, a visual artist herself, added. “Knowing that the government will most likely not provide economic support, artists on the island still continue to create and collaborate with each other.” In her view, the Puerto Rican artists working this way show “a commitment that defies capitalism:” continuing to craft their art, despite not having economic gain. The lack of government support, while irresponsible and unjust, has endured a culture of collaboration and resistance where Puerto Rican artists have chosen to follow their desires of creating arts under their own terms.

Finding sovereignty through art

Archivos del Caribe continues to produce free, accessible material on our social media accounts and website — which we paid for out of our own pockets and built ourselves. We chose to continue creating because, from within the organization, we are able to create contemporary material that is representative of us, unlike what we learned in our history classes. From dark-skinned people that were not shown in history books to “Nuyoricans,” we incorporate photos from all of the municipalities, economic backgrounds, genders, and races. Curating this space ourselves, for people who look like us, is already a rejection to the system. We are creating the space they have not given to us.

Many other groups have founded their own artistic spaces, like Archivos del Caribe, to reclaim the identities we have been forced to neglect through narratives ingrained in us since childhood. In our education system, we are taught in a ritualistic matter that we are a mixture of three races: Spanish, African, and Taíno. This misconception that is perpetuated is used in the Puerto Rican education system to assimilate to whiteness, as our white Latinx peers are encouraged to claim their Blackness through the narrative of the three races, but evidently Black-skinned people cannot say they are Black. Curly hair at my private high school is seen as bad hair. My mom always gets the random TSA inspection at the airport that is never really random. My grandma refers to her own nappy hair as grass because of the texture.

There are times when the racism is not intentional; it comes from centuries of colonized social practices, an internalized hatred for our own community. The government not declaring a state of emergency for the 37 women that have been killed by gender violence, including 6 trans women, hurricane María’s unattended long-lasting effects that still have people with blue awnings instead of a roof on their home, and Trump’s blatant attacks towards Puerto Ricans are some of the reasons the colonial status of the island feels heavier lately.

Even when noting the institutions that fail us, we choose to continue creating as a rejection of the abuse. Some of us create visually curated photography archives, others literary magazines, or still-life paintings. All of this occurs against a background of constantly consuming negative news about corruption from our political leaders, watching crime against women and trans folks rise, living in the uncertainty of what will happen next. We turn to art to survive. The arts are a form of creating justice for our histories and culture; a step closer to freeing ourselves from the institutional constraints. We have found power in spreading care, independently.

This article was written by Nicole Collazo Santana and edited by Camille Padilla Dalmau.