Police Swarmed Our LGTBQIA+ Club. Why?

Most LGBTQIA+ clubs, bars, coffee shops, and other gathering places — including pop-up events held at venues not specific to the community— aim to be safe spaces, also referred to as safer spaces. For those unfamiliar with the concept, broadly speaking, a safer space is one in which nobody is hurt or made to feel uncomfortable, be it physically, mentally, or emotionally. The term is mostly used in the context of nightlife but is not limited to those confines.

A 100 percent harm-free space, though, isn’t possible. There are simply too many variables, from the unknown entry of an aggressor to the possibility that a song played could upset someone (nobody wants to hear Chris Brown’s music, okay?) to the fact that, in a pandemic, the risk of contracting Covid-19 looms, even for the masked and vaccinated. By acknowledging the impossibility of the ideal, though, we can actually get closer to it: Safer, rather than safe, is a reminder to stay vigilant.

But nobody expects a group of 20 armed police officers to roll up on an LGBTQIA+ club. Not in 2021, right? Unfortunately, that’s what happened the night of Thursday, July 22, at Loverbar—the restaurant and bar I founded in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“We’re here to verify permits,” an officer informed me.

The group had marched down the Paseo de Diego, a pedestrian only commercial strip in the downtown area of Río Piedras, one of San Juan’s oldest neighborhoods and also home to the University of Río Piedras, as well as many of its students. Because I happened to be outside at 10:45 p.m. or so, I saw the authorities coming. My concern was elsewhere: Something awful must have happened nearby, I feared.

Wrong. Within seconds I realized the intimidating group of municipal officers, the bulk of them wearing dark camouflage, what I assume were bulletproof vests, and black hats, were clustering before the doors of Loverbar. They’d had to pass through about 30 people, the majority of them Loverbar customers and most of them queer and trans folks, who had previously been enjoying the company of their friends, drinking and laughing.

It’s important to provide context here, particularly for anyone unfamiliar with Puerto Rico’s police. It’s common knowledge that in the United States, many marginalized folks see police as threatening, frightening; the police are not, to many, the protectors of the people they purport to be. A lot of Puerto Ricans feel similarly about their country’s own: serious problems include, though are not limited to, attacks on and murders of unarmed people and, quite notoriously, the unnecessary use of force and targeted repression of protests — from the ‘70s to the #RickyRenuncia movement to recent demonstrations against environmentally harmful construction plans in the municipality of Rincón.

And so of course, the agglomeration of these agents scared me. But as the founder of Loverbar, it is obviously my responsibility to intervene. Additionally, being a cisgender, straight-passing, white Latina, and considering the history of police violence against more “othered” identities, I would count myself among the least vulnerable of the group facing these police. Anxieties notwithstanding, I had to act.

“I’ll take you right to the permits,” I told them, and I did.

About 10 officers entered Loverbar along with the permits officer. I wasn’t expecting that; why should the cops come inside? The rest stayed outside, blocking the entrance, most with hands on their guns. All of them, both inside and outside Loverbar, looked ready for action.

What kind of action they expected, I don’t know. Loverbar is a community space. There are signs outside and inside about respecting people’s pronouns and loving and respecting each other. There’s a mural just inside — you can’t miss it — denouncing homophobia, transphobia, and racism. The space is mostly pink, with vintage curios and knicknacks all over. A trans flag and a pride flag hang as focal points on the mezzanine from which the DJ is typically stationed.

The juxtaposition of the dark storm of an armed police crowd against our love-centric, cutesy decor will be seared in my memory forever, alongside the throb of a sinking stomach as I realized that night, in real time, how traumatic this surreal event would be for everyone present.

Johni JacksonTweet

Because this information is available virtually to the office of permits, the representative probably already knew this: Our permits are up to date. There was one problem, though: We’d closed the kitchen early that night, and we didn’t realize our permit only allows us to operate the bar while the kitchen is open. Later our lawyer told us a lapse of one hour during which no food orders are taken but the bar still operates is allowed, but that wouldn’t have helped last Thursday anyway. The kitchen had stopped taking orders shortly before 10 p.m. We were fined $2,000 on this technicality. I accept that; lesson learned. It’s not the fine that’s the problem—although I do have lots of feelings about the treatment of and lack of support for small businesses by the government. But the main issue, obviously, is the manner in which this permit-checking process was realized.

While filling out our paperwork that night, the permits officer told me that someone had filed a complaint against us. She also told me that the information is public. I’ve been told by two people, a local business owner and a community leader, that it’s a neighbor of Río Piedras who made the complaint, and cited several other local restaurants and bars. I hope to read the official documents with my own eyes very soon.

But of the other businesses that were also “checked” that night, it is my understanding, after talking with the owner and manager, respectively, of two nearby nightlife establishments that were also visited by the police and a permits officer the same night, that none of them received such heavy-handed treatment as Loverbar. Why?

We deserve safer spaces

The LGBTQIA+ community — and all marginalized peoples — deserve safer spaces. They deserve respites from a society that responds to their very exist with discrimination, oppression, and violence. But this absurd quantity of officers, with their huge guns and stoic expressions? They completely obliterated the feeling of security we’ve worked so hard to cultivate at Loverbar. (To be truthful, not all the officers were so stolid. Two of them, at one point, were laughing.)

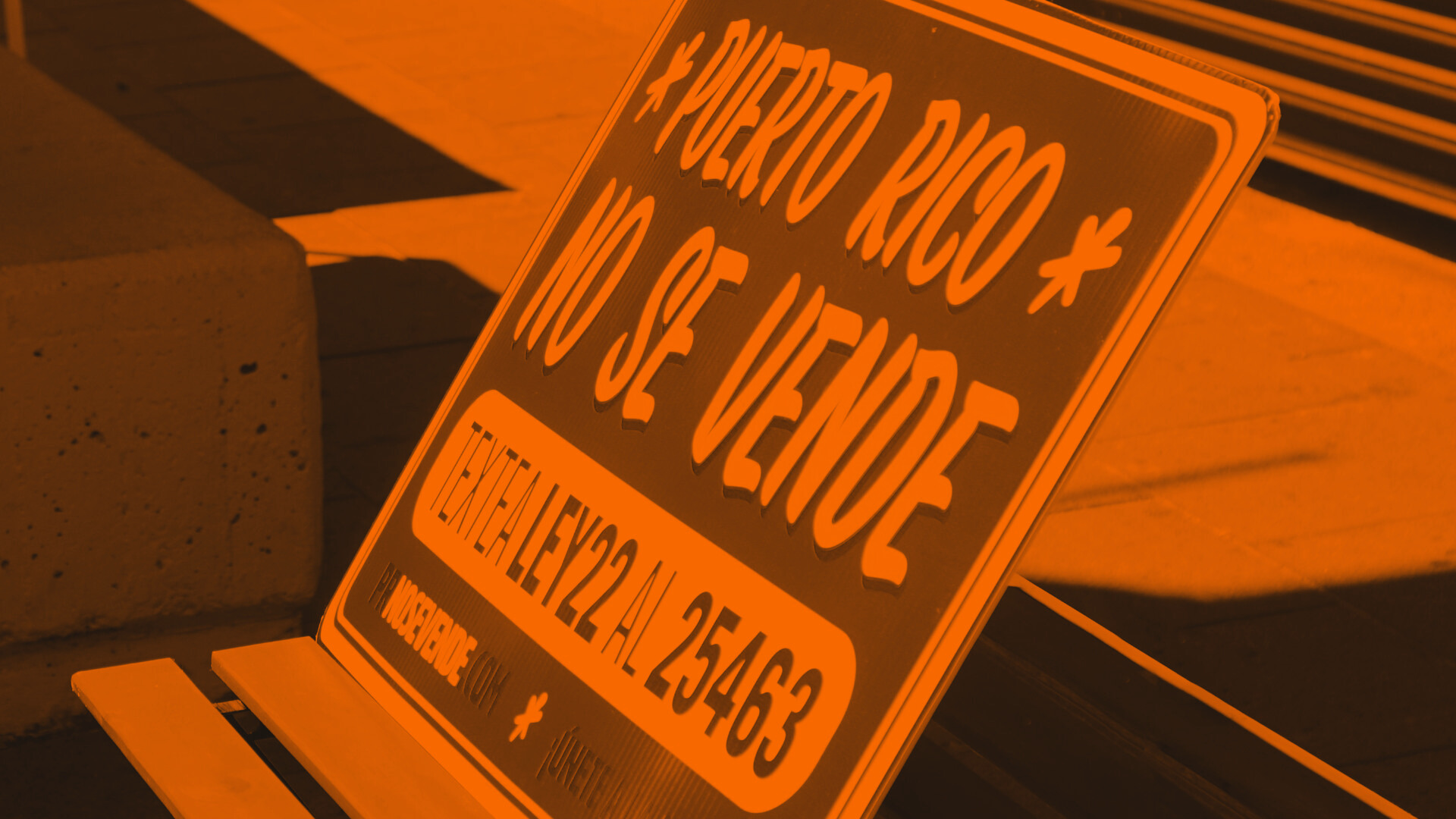

Of all the U.S. states and its territories or colonies, Puerto Rico ranks highest in murders of transgender and gender non-conforming people. Here, LGBTQIA+ people face discrimination on the daily; religious conservatism is widespread. Any prejudice negatively affects employment possibilities, especially for trans and gender nonconforming people, especially if they are Black or not white-passing Latinxs. Unemployment in Puerto Rico has for years hovered between 40 and 50 percent, and so while there’s no statistics specific to LGBTQIA+ residents on this, we can safely assume, especially if U.S. data is any indication, that for our community, the rate is most certainly higher.

A completely safe space is impossible; I will readily admit that. But every single day, as a team, we try our damndest to get there. That effort is what makes us a place where LGBTQIA+ people can more readily thrive, where they can more comfortably be themselves, fully and happily.

Jhoni JacksonTweet

That night, like most everyone present, my anxiety hit an unprecedented high. And I felt so small when, once I knew we were fined and the ordeal was coming to an end, I asked the officers, “Why did you need the guns?”

Their answer? The whole thing, guns and all, is protocol. As frightening as that sounds, all things considered, it makes sense: for all marginalized people, the unnecessary use of force by police is most definitely protocol.

We are very lucky that nobody was physically hurt. We are fortunate, too, to have our community’s support. Not only have many donated generously to help us pay the fine, but also they’re publicly condemning the actions of the police that night. The mayor of San Juan, a conservative, at first called the condemnations rumors. He soon after backpedaled, declaring publicly that he’d ordered an investigation into the events of the night.

Nearly one month later, on Aug. 11, I hadn’t heard from Romero’s office, and so I emailed directly asking about the status of said investigation. I received a response on Aug. 26 from an attorney who explained she was contracted on June 30 by Romero’s office to lead this investigation.

When asked to meet with her on Aug. 26, I agreed, and subsequently spent an hour answering her questions in what looked like a storage room inside the Permits Office of San Juan. Boxes full of paperwork piled high all around us — myself, a consultant of Loverbar who’s been helping us through this situation, and the attorney — I responded with as much detail as possible. But no, I couldn’t remember the name of the officer whose hands were so close to my face I had to step back. I did remember, however, the anxiety I felt when asking the group of armed officers inside Loverbar why they needed their guns. I relayed to her what I’ve recounted here: that I was told such force is “protocol.”

The attorney asked what I wanted out of this situation; I told her, among other things, that I want this protocol changed. No business should have to endure the anxiety of a multitude of armed officers entering their premises without cause. Imagine if they’d done this at a corporate chain, like an Olive Garden, I said. It would never happen. So why does it happen to independent businesses?

The peace at Loverbar that night was undeniably violated, and it will take us — employees, community members — time to recuperate from the trauma of the event. To be honest, I think nobody who was there will ever forget how they felt then, be that emotion rage or fear or a combination of many others.

But Loverbar will not close its doors because of this. For as long as possible, and despite whatever difficulties or discriminations come our way, we will continue our mission to cultivate a safer space for all.

Jhoni Jackson